Can we touch the future? Can we feel it?

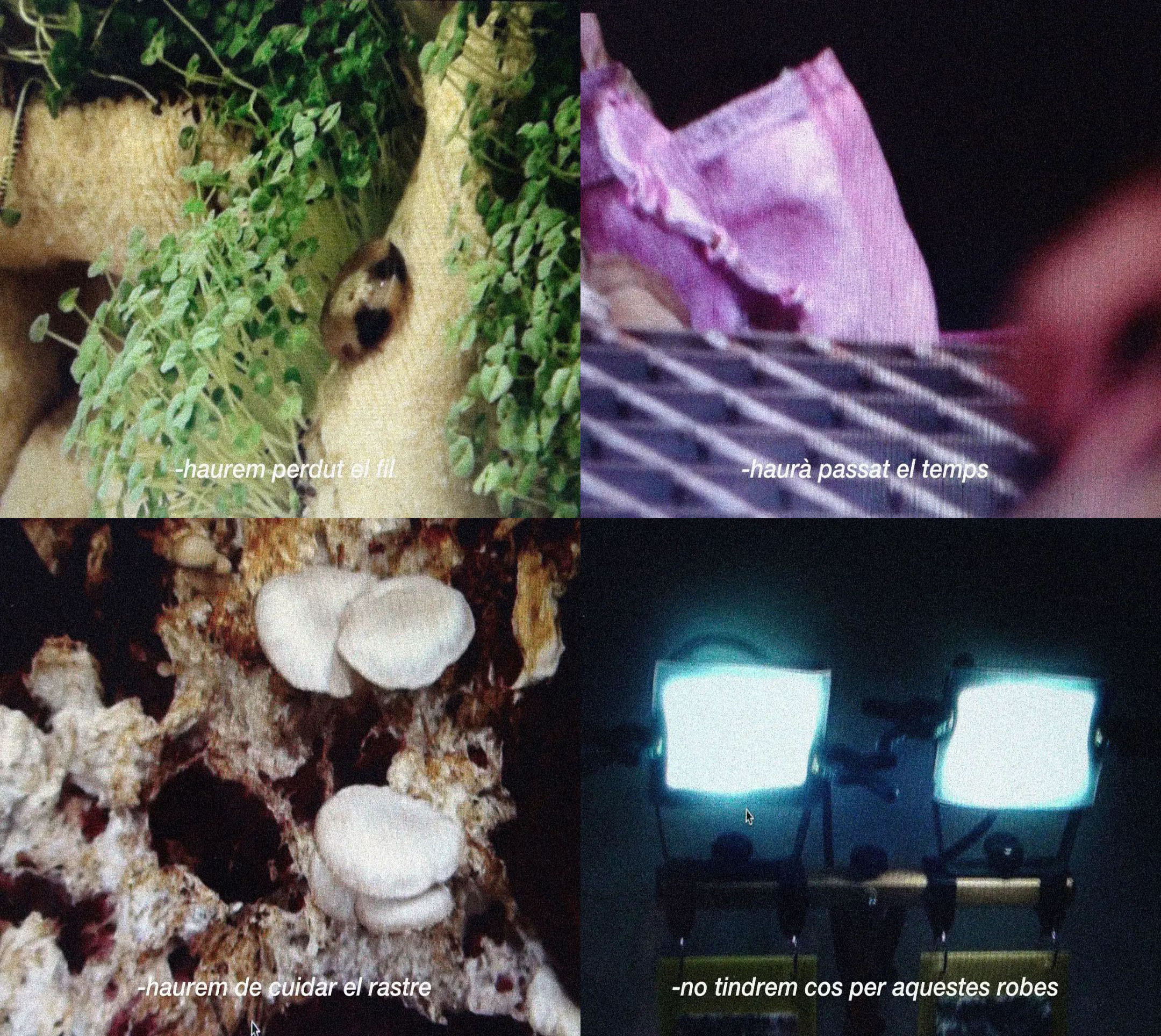

Like a contradiction, CROP invites us to discover the future on an archaeological site. Teatre Nacional de Catalunya, year 2053. The main theatre institution of Catalonia opens its doors to us so that we can appreciate some items of its historical costumes; and with them, as if by chance, the indefinite step from archive to storehouse1, storehouse, from storehouse to remains. That which is so close to a nothingness. It is there where we can look at each item and its context. The labels – what else? − tell us about their coordinates. Also a voice, speaking to us in our ear through headphones. The fabric can be torn up or turn mouldy. Despite time, we can sense the misfortune. On the fabric there can be pandemics, fires, floods, great classics. The fabric is not the future, but it can contain traces of it.

1

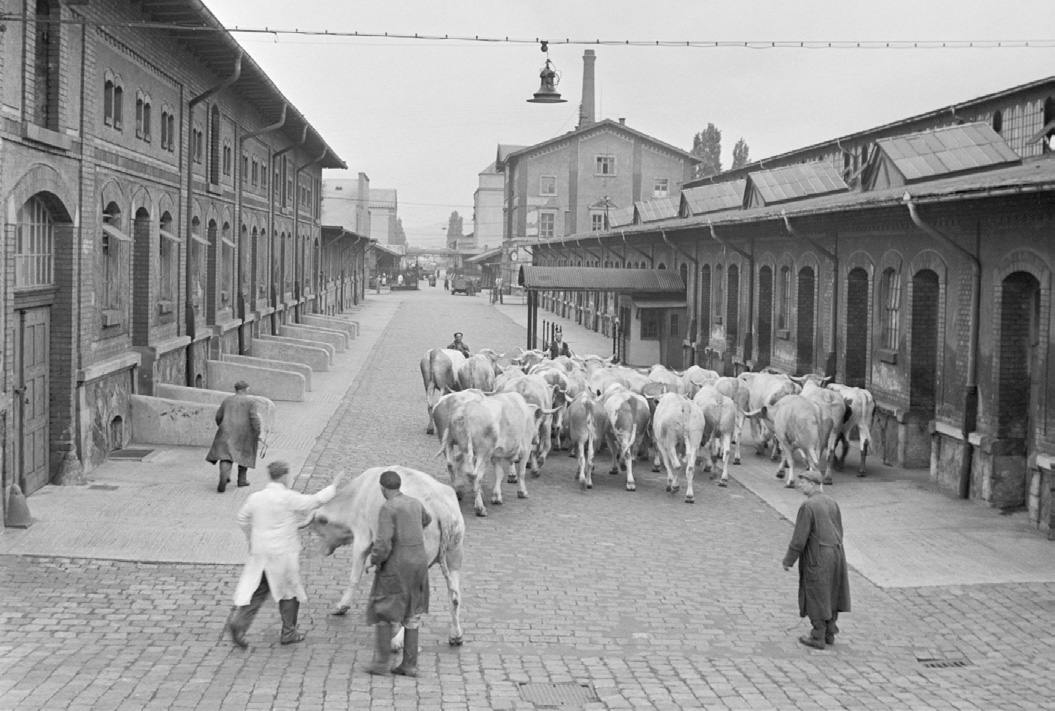

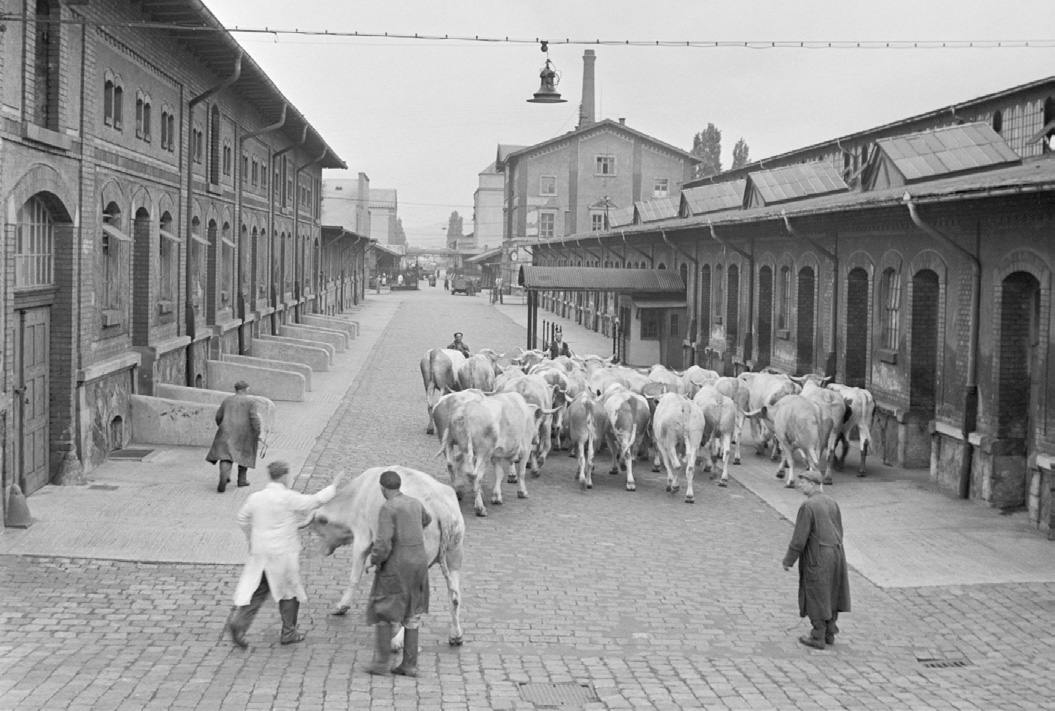

The space where CROP is exhibited is not innocent. It is Hall number 11 of the old municipal slaughterhouse in Prague, located in District 7, north of the river. Upon entering, to the right. Once an industrial suburb, today it is a magnetic center for artistic proposals and exhibitions. The changes in the use of the Holešovice market and slaughterhouse are also proof of culture as a form of evolution, perversion, speculation, and survival. Where once lambs, cows, or pigs were slaughtered and sold, now the scenographies of the future are dissected.

2

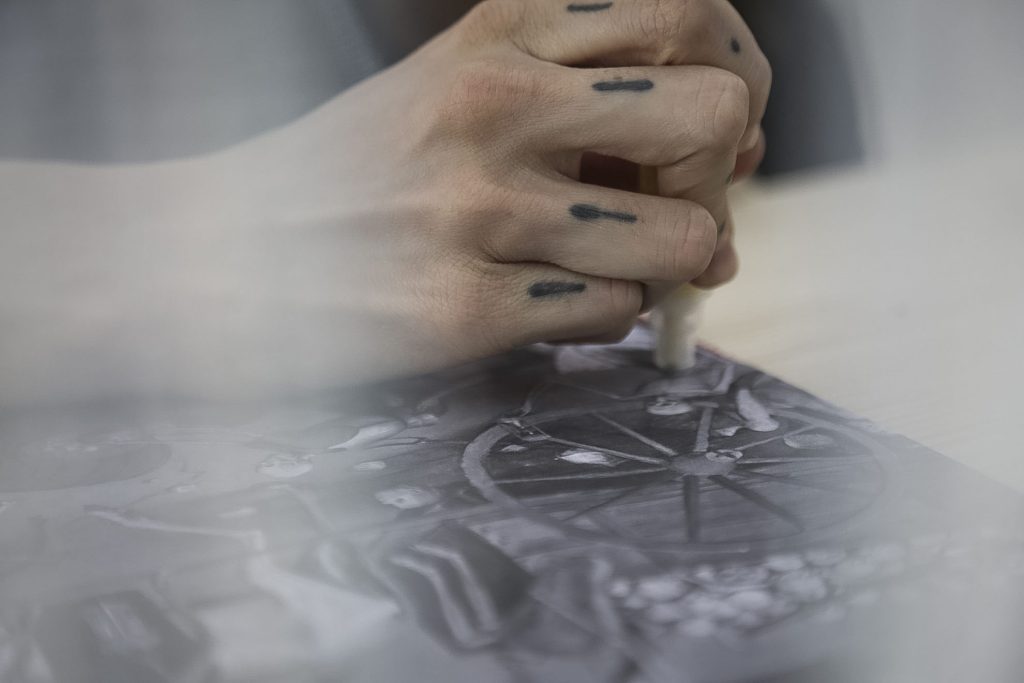

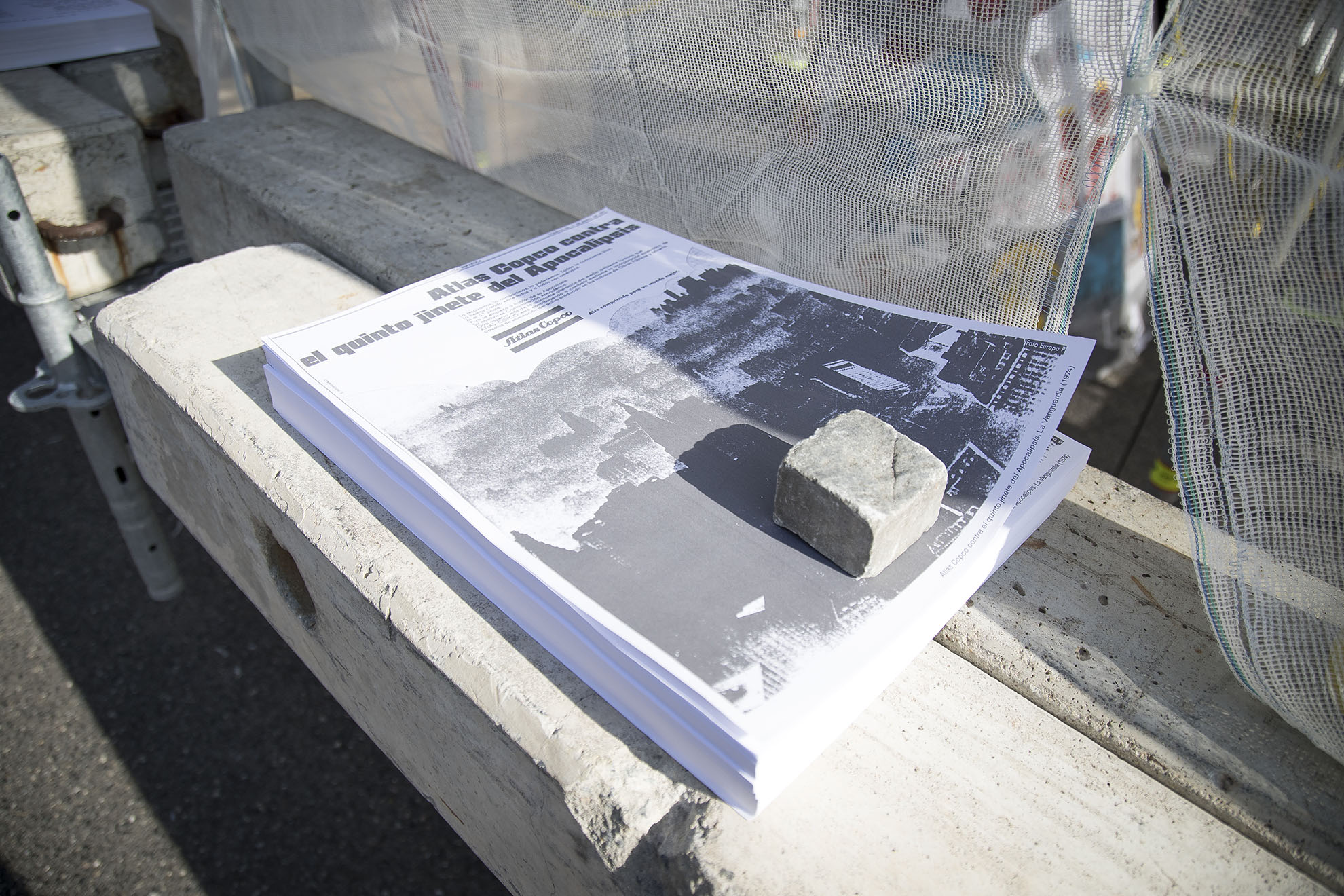

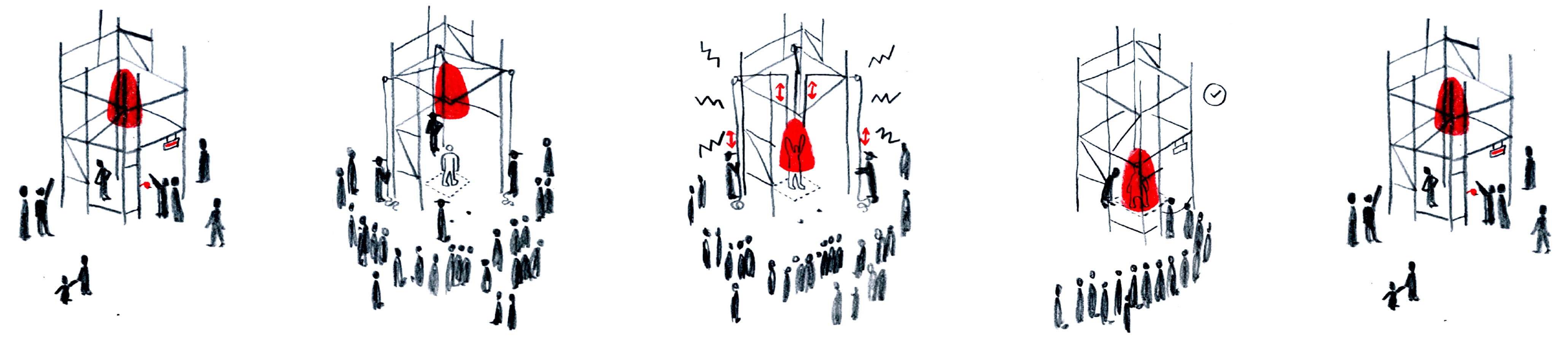

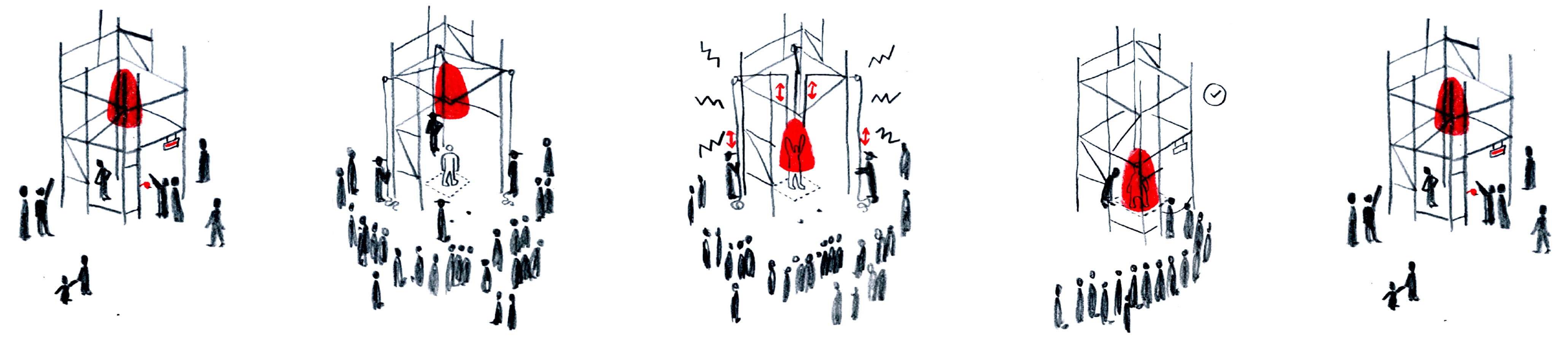

The panel inviting you to enter The Chant of the Sybil is vertical and made of plastic. It flutters in the wind. Six icons with the aesthetics of building construction signs accompany six instructions: "choose an image," says the first, showing a pile of papers circled in red. The second says "recognize the Sibyl" and depicts, in white against the blue of obligation, the cloak upon which much of the installation's weight falls. Then it says "choose your tools," showing a pencil and a brush like those spectators or users will find inside. "Declare your prophecy," it continues, drawing a question mark inside a yellow emergency or danger triangle. Two figures stick the papers onto the cloak: "attach it to the garment." And finally, another triangle, also in the color of danger: "the garment will ascend to dress the future." Between stitches or between frames, the clothing of the future is written in each work.

3

The people say, "Time flies." They write, "there is no future." "Divide and conquer," whispers someone else. Above the lyrics of the Sibyl of Lluc and the Cathedral, a vibrant drawing of a God almost in majesty. "The only certainty, death." "Constellation of death." And on the same paper, written over drawings and more words: "How much longer? Is it still far? I'm hungry. I need to pee. I want to go down." Another whispers, at one end, "I love you." And more: "Respect death." "We've forgotten everything." "How will we get through this?" "Is there anything that really matters?" Someone attaches an old photo of their grandparents. A girl intervenes too. She spends forty minutes drawing and writing. She writes her name. Draws a cloud above it, the bitter water, and below it, the first sprouts of a life striving to see. "Josephine" with roots and leaves. Her end of the world, her name. Only names remain.

4

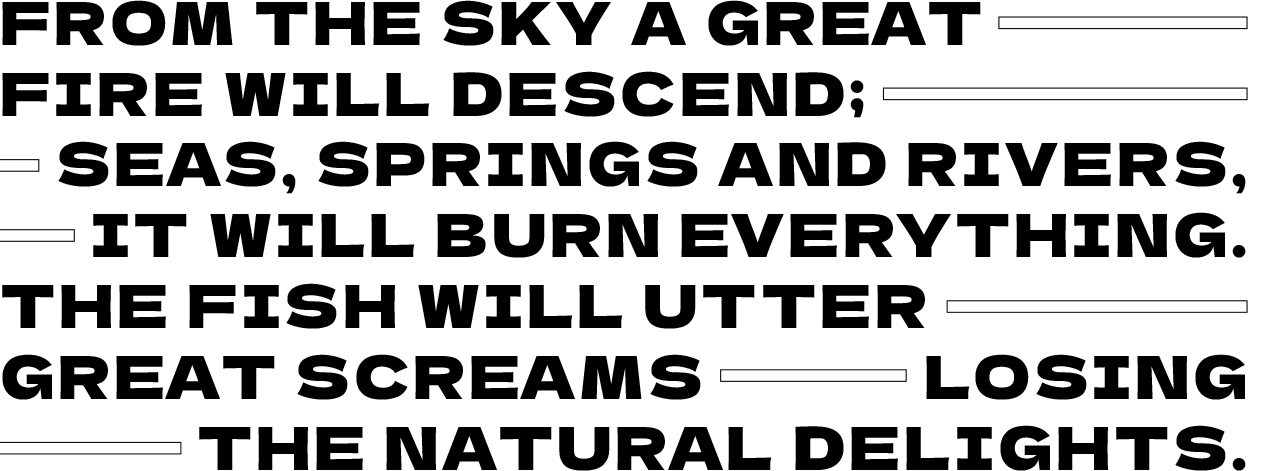

«From the sky a great fire will descend;

seas, springs and rivers, it will burn everything.

The fish will utter great screams

losing the natural delights.»

The Chant of the Sybil

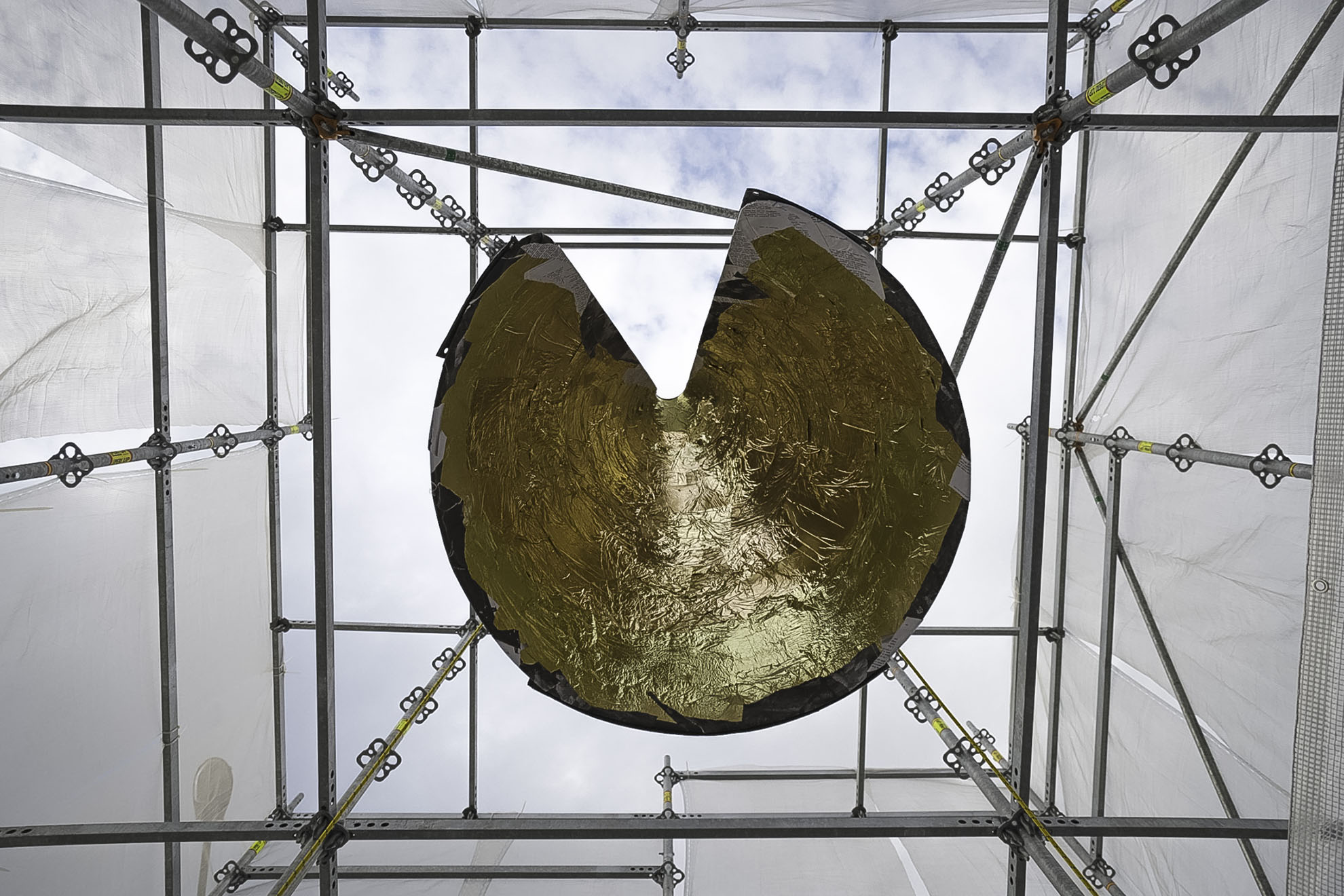

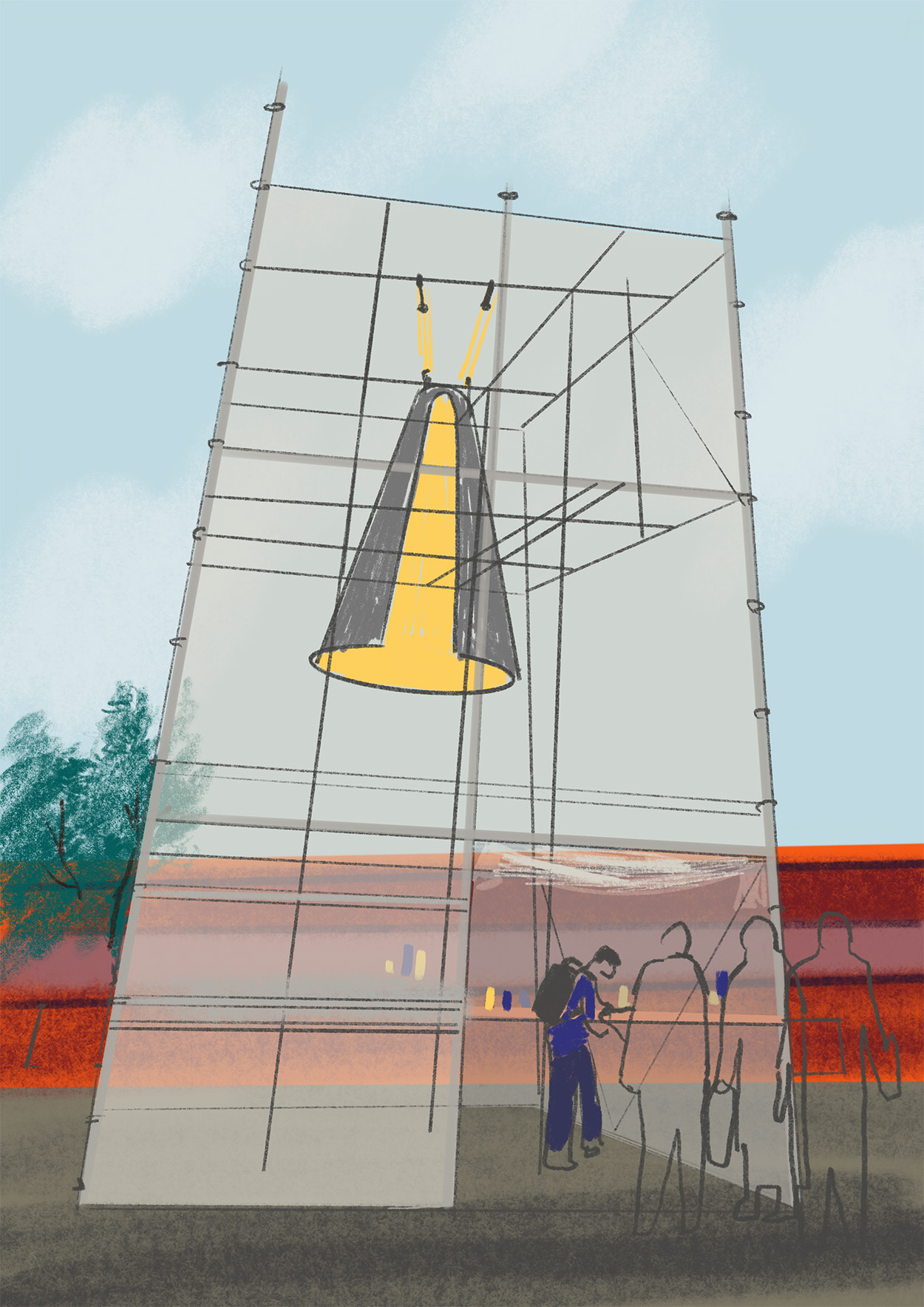

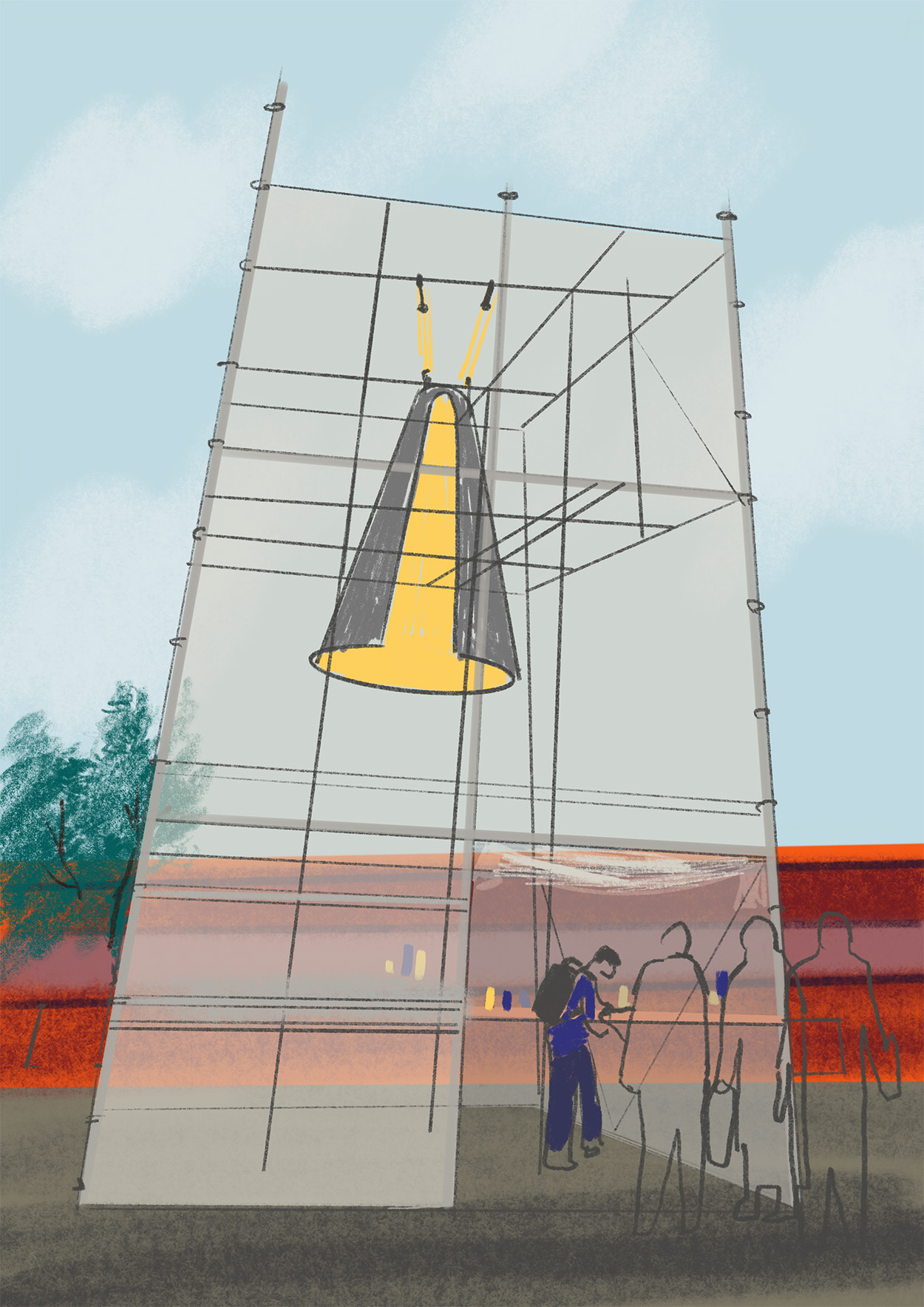

To write, paste, paint, touch and spread the traces of this future: this is the purpose of “The Chant of the Sybil”. There is a scaffold, protected by the translucent screen of some veils. "Inside rests the Sibyl", says a sign above the door. Beside it, some instructions.2 Inside, there is a cloak hanging, which, through a sophisticated system of pulleys, descends at the precise time until reaching the level of the spectator. It is then when the maxim that inspires this installation is materialised: “Anyone of us can be the Sybil”. By intervening3, whether by writing on or assembling a new layer of glued paper, it is we who herald and project the Apocalypse. Once the time has come, what landscape4 will our eyes see?

5

Evoking and representing the universe of a sound without always making it present is one of the many purposes of The Chant of the Sybil. Occasionally, whether at noon or at four in the afternoon, the technical and artistic team activates the sound. It reverberates from above, fractured, crowning the tower of stitches and canopies that at times is a tower and at times a bell tower, tent, pulpit, watchtower, minaret. Like an invitation to nothingness, or to reflection, the speakers vibrate with harmonious melodies and Lo-fi tones. Moments later, a distorted song: is it from a child or a woman? Can anyone guarantee that it is human, when deity and person coincide in the voice of prophecy? Thus, the entire square feels the song, interspersed with brief and florid organ interludes. And once the cloak descends, what was once music now reproduces voice cuts from news broadcasts: floods, fires, pandemics, poverty, housing emergencies. "Should we be concerned?" questions the voice of an interviewer. The interviewee hesitates for a moment, clears their throat, resumes the conversation with a tremulous voice: "Yes, we should be concerned." What effect must it have to hear bad news in a language that is not understood?

6

All the things that I don't

that I don't know how to explain

all the things that I don't

uhmmmm…

Arnal, Maria; & Bagés, Marcel.

«Hiperutopia» [song],

from the album Clamor.

Barcelona: Fina Estampa, 2021.

The Chant

of the Sybil

Raimon Rius

CROP

Raimon Rius

CROP

Raimon Rius

The Chant

of the Sybil

Raimon Rius

INSTRUCTIONS

The panel inviting you to enter The Chant of the Sybil is vertical and made of plastic. It flutters in the wind. Six icons with the aesthetics of building construction signs accompany six instructions: "choose an image," says the first, showing a pile of papers circled in red. The second says "recognize the Sibyl" and depicts, in white against the blue of obligation, the cloak upon which much of the installation's weight falls. Then it says "choose your tools," showing a pencil and a brush like those spectators or users will find inside. "Declare your prophecy," it continues, drawing a question mark inside a yellow emergency or danger triangle. Two figures stick the papers onto the cloak: "attach it to the garment." And finally, another triangle, also in the color of danger: "the garment will ascend to dress the future." Between stitches or between frames, the clothing of the future is written in each work.

INTERVENTION

The people say, "Time flies." They write, "there is no future." "Divide and conquer," whispers someone else. Above the lyrics of the Sibyl of Lluc and the Cathedral, a vibrant drawing of a God almost in majesty. "The only certainty, death." "Constellation of death." And on the same paper, written over drawings and more words: "How much longer? Is it still far? I'm hungry. I need to pee. I want to go down." Another whispers, at one end, "I love you." And more: "Respect death." "We've forgotten everything." "How will we get through this?" "Is there anything that really matters?" Someone attaches an old photo of their grandparents. A girl intervenes too. She spends forty minutes drawing and writing. She writes her name. Draws a cloud above it, the bitter water, and below it, the first sprouts of a life striving to see. "Josephine" with roots and leaves. Her end of the world, her name. Only names remain.

SOUND

Evoking and representing the universe of a sound without always making it present is one of the many purposes of The Chant of the Sybil. Promptly, whether at noon or at four in the afternoon, the technical and artistic team activates the sound. It reverberates from above, fractured, crowning the tower of stitches and canopies that at times is a tower and at times a bell tower, tent, pulpit, watchtower, minaret. Like an invitation to nothingness, or to reflection, the speakers vibrate with harmonious melodies and Lo-fi tones. Moments later, a distorted song: is it from a child or a woman? Can anyone guarantee that it is human, when deity and person coincide in the voice of prophecy? Thus, the entire square feels the song, interspersed with brief and florid organ interludes. And once the cloak descends, what was once music now reproduces voice cuts from news broadcasts: floods, fires, pandemics, poverty, housing emergencies. "Should we be concerned?" questions the voice of an interviewer. The interviewee hesitates for a moment, clears their throat, resumes the conversation with a tremulous voice: "Yes, we should be concerned." What effect must it have to hear bad news in a language that is not understood?

Sebastià Portell

The Chant of the Sybil #1, Elena Molina

The Chant of the Sybil #2, Elena Molina

Can we touch the future? Can we feel it?

Like a contradiction, CROP invites us to discover the future on an archaeological site. Teatre Nacional de Catalunya, year 2053. The main theatre institution of Catalonia opens its doors to us so that we can appreciate some items of its historical costumes; and with them, as if by chance, the indefinite step from archive to storehouse1, storehouse, from storehouse to remains. That which is so close to a nothingness. It is there where we can look at each item and its context. The labels – what else? − tell us about their coordinates. Also a voice, speaking to us in our ear through headphones. The fabric can be torn up or turn mouldy. Despite time, we can sense the misfortune. On the fabric there can be pandemics, fires, floods, great classics. The fabric is not the future, but it can contain traces of it.

To write, paste, paint, touch and spread the traces of this future: this is the purpose of “The Chant of the Sybil”. There is a scaffold, protected by the translucent screen of some veils. "Inside rests the Sibyl", says a sign above the door. Beside it, some instructions.2 Inside, there is a cloak hanging, which, through a sophisticated system of pulleys, descends at the precise time until reaching the level of the spectator. It is then when the maxim that inspires this installation is materialised: “Anyone of us can be the Sybil”. By intervening3, whether by writing on or assembling a new layer of glued paper, it is we who herald and project the Apocalypse. Once the time has come, what landscape4 will our eyes see?

1

The space where CROP is exhibited is not innocent. It is Hall number 11 of the old municipal slaughterhouse in Prague, located in District 7, north of the river. Upon entering, to the right. Once an industrial suburb, today it is a magnetic center for artistic proposals and exhibitions. The changes in the use of the Holešovice market and slaughterhouse are also proof of culture as a form of evolution, perversion, speculation, and survival. Where once lambs, cows, or pigs were slaughtered and sold, now the scenographies of the future are dissected.

2

The panel inviting you to enter The Chant of the Sybil is vertical and made of plastic. It flutters in the wind. Six icons with the aesthetics of building construction signs accompany six instructions: "choose an image," says the first, showing a pile of papers circled in red. The second says "recognize the Sibyl" and depicts, in white against the blue of obligation, the cloak upon which much of the installation's weight falls. Then it says "choose your tools," showing a pencil and a brush like those spectators or users will find inside. "Declare your prophecy," it continues, drawing a question mark inside a yellow emergency or danger triangle. Two figures stick the papers onto the cloak: "attach it to the garment." And finally, another triangle, also in the color of danger: "the garment will ascend to dress the future." Between stitches or between frames, the clothing of the future is written in each work.

3

The people say, "Time flies." They write, "there is no future." "Divide and conquer," whispers someone else. Above the lyrics of the Sibyl of Lluc and the Cathedral, a vibrant drawing of a God almost in majesty. "The only certainty, death." "Constellation of death." And on the same paper, written over drawings and more words: "How much longer? Is it still far? I'm hungry. I need to pee. I want to go down." Another whispers, at one end, "I love you." And more: "Respect death." "We've forgotten everything." "How will we get through this?" "Is there anything that really matters?" Someone attaches an old photo of their grandparents. A girl intervenes too. She spends forty minutes drawing and writing. She writes her name. Draws a cloud above it, the bitter water, and below it, the first sprouts of a life striving to see. "Josephine" with roots and leaves. Her end of the world, her name. Only names remain.

4

«From the sky a great fire will descend;

seas, springs and rivers, it will burn everything.

The fish will utter great screams

losing the natural delights.»

The Chant of the Sybil

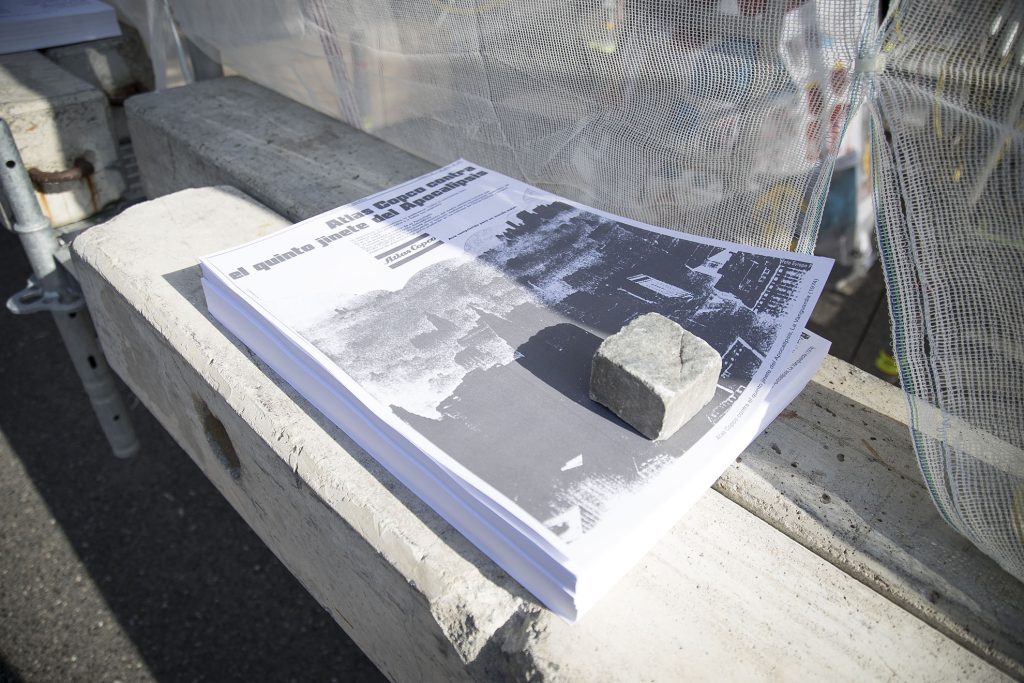

CROP, David Corral

5

Evoking and representing the universe of a sound without always making it present is one of the many purposes of The Chant of the Sybil. Occasionally, whether at noon or at four in the afternoon, the technical and artistic team activates the sound. It reverberates from above, fractured, crowning the tower of stitches and canopies that at times is a tower and at times a bell tower, tent, pulpit, watchtower, minaret. Like an invitation to nothingness, or to reflection, the speakers vibrate with harmonious melodies and Lo-fi tones. Moments later, a distorted song: is it from a child or a woman? Can anyone guarantee that it is human, when deity and person coincide in the voice of prophecy? Thus, the entire square feels the song, interspersed with brief and florid organ interludes. And once the cloak descends, what was once music now reproduces voice cuts from news broadcasts: floods, fires, pandemics, poverty, housing emergencies. "Should we be concerned?" questions the voice of an interviewer. The interviewee hesitates for a moment, clears their throat, resumes the conversation with a tremulous voice: "Yes, we should be concerned." What effect must it have to hear bad news in a language that is not understood?

6

All the things that I don't

that I don't know how to explain

all the things that I don't

uhmmmm…

Arnal, Maria; & Bagés, Marcel.

«Hiperutopia» [song],

from the album Clamor.

Barcelona: Fina Estampa, 2021.

Drawings by Raimon Rius

INSTRUCTIONS

The panel inviting you to enter The Chant of the Sybil is vertical and made of plastic. It flutters in the wind. Six icons with the aesthetics of building construction signs accompany six instructions: "choose an image," says the first, showing a pile of papers circled in red. The second says "recognize the Sibyl" and depicts, in white against the blue of obligation, the cloak upon which much of the installation's weight falls. Then it says "choose your tools," showing a pencil and a brush like those spectators or users will find inside. "Declare your prophecy," it continues, drawing a question mark inside a yellow emergency or danger triangle. Two figures stick the papers onto the cloak: "attach it to the garment." And finally, another triangle, also in the color of danger: "the garment will ascend to dress the future." Between stitches or between frames, the clothing of the future is written in each work.

INTERVENTION

The people say, "Time flies." They write, "there is no future." "Divide and conquer," whispers someone else. Above the lyrics of the Sibyl of Lluc and the Cathedral, a vibrant drawing of a God almost in majesty. "The only certainty, death." "Constellation of death." And on the same paper, written over drawings and more words: "How much longer? Is it still far? I'm hungry. I need to pee. I want to go down." Another whispers, at one end, "I love you." And more: "Respect death." "We've forgotten everything." "How will we get through this?" "Is there anything that really matters?" Someone attaches an old photo of their grandparents. A girl intervenes too. She spends forty minutes drawing and writing. She writes her name. Draws a cloud above it, the bitter water, and below it, the first sprouts of a life striving to see. "Josephine" with roots and leaves. Her end of the world, her name. Only names remain.

SOUND

Evoking and representing the universe of a sound without always making it present is one of the many purposes of The Chant of the Sybil. Promptly, whether at noon or at four in the afternoon, the technical and artistic team activates the sound. It reverberates from above, fractured, crowning the tower of stitches and canopies that at times is a tower and at times a bell tower, tent, pulpit, watchtower, minaret. Like an invitation to nothingness, or to reflection, the speakers vibrate with harmonious melodies and Lo-fi tones. Moments later, a distorted song: is it from a child or a woman? Can anyone guarantee that it is human, when deity and person coincide in the voice of prophecy? Thus, the entire square feels the song, interspersed with brief and florid organ interludes. And once the cloak descends, what was once music now reproduces voice cuts from news broadcasts: floods, fires, pandemics, poverty, housing emergencies. "Should we be concerned?" questions the voice of an interviewer. The interviewee hesitates for a moment, clears their throat, resumes the conversation with a tremulous voice: "Yes, we should be concerned." What effect must it have to hear bad news in a language that is not understood?

Sebastià Portell

The Chant of the Sybil, David Corral